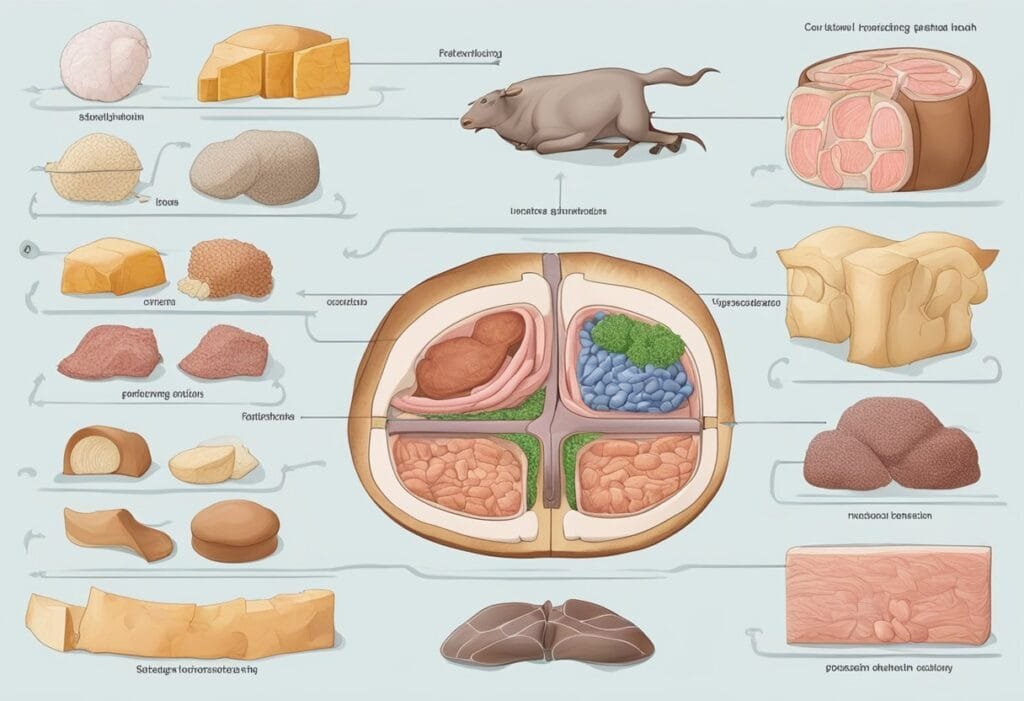

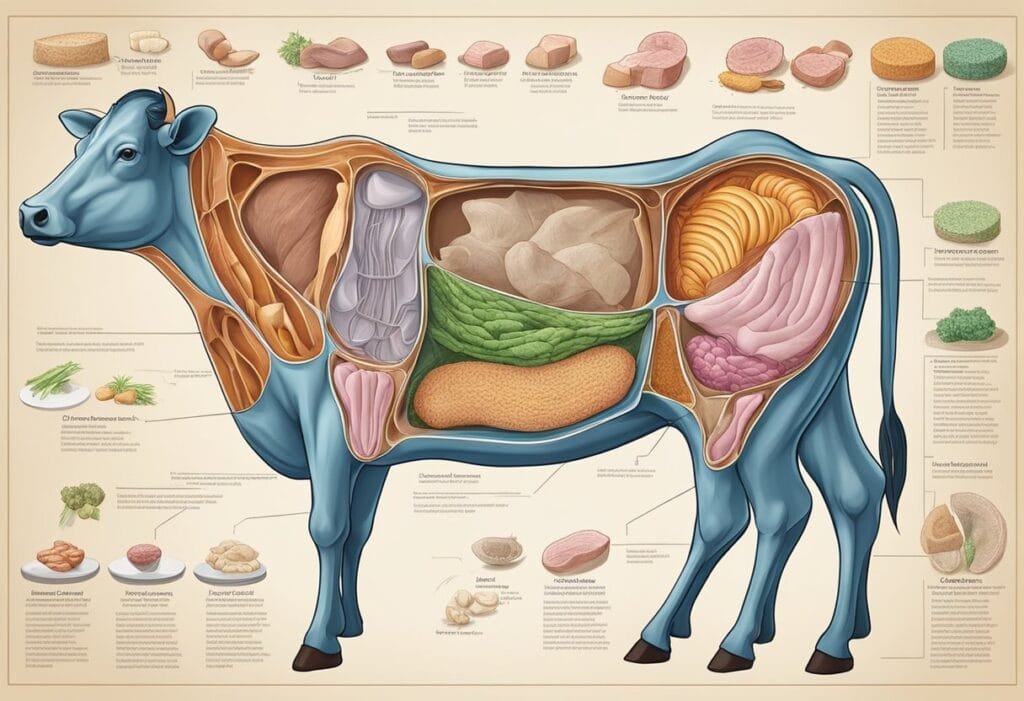

Cattle are ruminants, meaning they have a specialized stomach of cattle designed to efficiently break down fibrous plant material. The stomach of cattle consists of four compartments: the rumen, reticulum, omasum, and abomasum. Each compartment plays a distinct and essential role in digestion, allowing cattle to utilize cellulose-rich feedstuffs like grass, hay, and silage. Here’s an in-depth explanation of each compartment and how they work together.

1. The Rumen: The Fermentation Vat

Structure

- Size: The largest compartment, comprising about 60-70% of the total stomach volume in mature cattle (approximately 40-50 gallons in large animals).

- Anatomy: Located on the left side of the abdomen, the rumen’s interior is lined with tiny, finger-like projections called papillae, which increase surface area for absorption.

Function

- The rumen serves as a fermentation chamber where microbes (bacteria, protozoa, fungi) break down complex plant carbohydrates, particularly cellulose and hemicellulose.

Processes

- Microbial Fermentation: Microorganisms produce enzymes that break down plant fibers into volatile fatty acids (VFAs), including acetate, propionate, and butyrate. These VFAs are absorbed through the rumen wall and serve as the primary energy source for cattle.

- Protein Synthesis: Microbes synthesize microbial protein by utilizing nitrogen from dietary protein and non-protein nitrogen sources (like urea).

- Methane Production: A by-product of fermentation, methane is expelled through eructation (belching).

Key Features

- Continuous Mixing: Contractions of the rumen wall mix the contents, ensuring efficient fermentation.

- pH Maintenance: The rumen operates best at a pH of 6.0-7.0. Saliva, rich in bicarbonates, buffers the rumen to maintain this pH.

2. The Reticulum: The Honeycomb

Structure

- Size: Smallest compartment, holding about 2-5 gallons.

- Anatomy: Located near the heart, just beneath the diaphragm, and connected to the rumen. Its interior resembles a honeycomb structure.

Function

- The reticulum works in tandem with the rumen to trap dense, undigested materials and small foreign objects (e.g., wires or nails).

- It plays a key role in the process of rumination (cud-chewing).

Processes

- Sorting and Filtering: Dense particles and indigestible materials are retained here, while lighter, more digestible material is sent back to the rumen or onward to the omasum.

- Rumination Initiation: The reticulum pushes partially digested feed back into the esophagus, allowing cattle to chew the cud, breaking down particles further and mixing them with saliva.

Diseases

- Hardware Disease: Sharp objects accidentally ingested can puncture the reticulum, causing infection and inflammation (traumatic reticuloperitonitis). Magnets are often given to cattle to prevent this.

Read about Cattle Nutrition.

3. The Omasum: The Leaf Pages

Structure

- Size: Holds about 4-10 gallons.

- Anatomy: Located to the right of the rumen, the omasum is spherical and contains numerous thin folds or “leaves” that resemble the pages of a book.

Function

- The omasum acts as a filter, ensuring that only finely ground material passes to the abomasum.

- It plays a role in water absorption and further reduces particle size.

Processes

- Water and VFA Absorption: The omasum absorbs significant amounts of water and some volatile fatty acids.

- Mechanical Grinding: The muscular folds break down ingested particles further, increasing the surface area for enzymatic action in the abomasum.

4. The Abomasum: The True Stomach Of Cattle

Structure

- Size: Holds about 5-7 gallons.

- Anatomy: Located below and behind the omasum, it closely resembles the stomach of non-ruminants. Its interior secretes digestive enzymes and acids.

Function

- The abomasum is the glandular stomach where chemical digestion begins, breaking down proteins and other nutrients into forms that can be absorbed in the small intestine.

Processes

- Enzyme Secretion: Pepsin and lipase break down proteins and fats.

- Acidic Environment: Hydrochloric acid (HCl) lowers the pH to around 2.0, killing microbes and denaturing proteins for easier digestion.

- Microbial Digestion: Microbial protein synthesized in the rumen is digested here, providing high-quality protein for the animal.

Key Features

- The abomasum prepares feed for the next stage of digestion in the intestines.

- Diseases:

- Displaced Abomasum: The abomasum can shift position, leading to digestive blockages and reduced feed intake.

5. Coordination Among Compartments

The compartments work together seamlessly:

- Ingestion: Cattle consume fibrous plant material.

- Fermentation (Rumen & Reticulum): Microbes break down fibers into VFAs; particles are sorted, regurgitated, and rechewed.

- Filtration (Omasum): Water is absorbed, and particles are finely ground.

- Enzymatic Digestion (Abomasum): Proteins and fats are broken down for absorption in the intestines.

6. Benefits of the Four-Compartment Stomach

- Efficient Utilization of Fibers: Ruminants can convert low-quality forages into high-quality protein and energy.

- Adaptability: The system allows cattle to thrive on a variety of feedstuffs, from grasses to grains.

- Microbial Symbiosis: Rumen microbes synthesize essential nutrients, including B vitamins and microbial protein, that enhance cattle nutrition.

Conclusion

The four-compartment stomach of cattle is a marvel of evolution, perfectly suited to extract nutrients from plant-based diets. Each compartment has a specific function, and their coordinated activity enables cattle to produce milk, meat, and energy efficiently. Understanding this system is crucial for effective cattle management, optimizing feed efficiency, and ensuring animal health.